Preparing the track at Arlington Raceway, Eastbourne.

BANGER BOYS OF BRITAIN

Amid a thick haze of exhaust fumes and the scream of revving engines, a pair of clapped out cars ram headlong into each other. The bumper hangs off one, whilst the other has lost both its rear wheels, barely recognisable as the Vauxhall Astra it once was. The race is over and Pikey Mikey's is the only car left moving. He can now disengage his victim, pick his way through the wreckage of his adversaries, and begin his victory lap.

Throughout south eastern England, Banger racers meet regularly to smash up the cars they have been working on all week. Stripped of normal features and fitted with re-enforcements, the cars are daubed in colourful paint and scrawled in slogans advertising junkyards, hair salons or messages to girlfriends. Racers travel from Eastbourne to Yarmouth, from Aldershot to Ipswich to take part - all with a banger strapped to the back of a truck. Drivers pour hard-earned cash and hours of physical labour into resuscitating a car to compete with and as the week progresses, excitement builds.

The infamous Destruction Derby epitomises the banger spirit. In this final race of the night, the oval track is turned into a figure of eight and the winner is the last car moving. This gladiatorial contest leaves the audience roaring with applause and falling about in hysterical laughter. Both driver and spectator visibly lust after this violent and explosive moment, which seems to satisfy a fundamental human instinct for destruction.

However, behind the reckless bravado is a surprising resourcefulness, entirely at odds with the 21st Century draw of consumerism. Whilst European governments are initiating schemes to encourage the purchase of new cars to kickstart flagging economies, this community bashes the dents out of misshapen door panels and reuses auto parts time and again in the most innovative ways. The lovingly painted vehicles look like relics from a traditional fairground as they are winched off the trucks with cranes - gaudy, joyful and quirky.

You only need to spend a couple of minutes in the pits to become aware of the codes of conduct, social hierarchies and strength of community that exists between racers. Many have started in childhood, growing up watching their parents race, and proudly continue the family tradition. Gang rivalries and feuds that fester between the teams are generally countered by an overall sense of camaraderie.

Some drivers say that the sport has kept them “off the streets” and it's easy to see why. Banger racing offers all the danger, machismo and gang mentality that a young person could want. Certainly, despite its costliness, the drama and violence that goes on inside the stadium allows the drivers to vent their frustration and exorcise a deep-seated need for combat - something that's probably inherent in all of us.

When I asked a number of racers whether they saw their sport as simultaneously creative and destructive. The response was always the same: “Nope. It’s just a good day out”.

Minutes before the first race, a driver is told to remove all broken glass from his windowpanes. The stadium managers at Wimbledon have complained that shards have been wounding the greyhounds, which use the same track on different nights of the week.

With the sound of roaring engines echoing out of the stadium, drivers wait patiently for their turn to enter. The racers say that adrenalin builds all week as they wait for this moment.

The first time I met Jimo, he took one look my camera and immediately hauled one of his friends onto the bonnet of a car, yanking down his trousers and revealing all. The second time, still playing for laughs, he dropped his own trousers, saying "you sure you've got a big enough lens for this?" These days he's much quieter; I think he's run out of things to say.

Alex (left) used to wreck about 50 cars a year. "That's a new banger every week! But I got bored with the sport when the drivers stopped hitting as hard." Now he just helps his friends in between races.

Steve is about to get married and has come to Aldershot for his stag party. All 15 of his friends are racing against him, and he is 'the target'.

After the rain.

The banger racing ethos is built on resourcefulness and functionality. Here, a misshapen panel is quickly bashed back into place.

Many young drivers grow up watching their fathers race, eventually getting their own cars and continuing the family tradition. Luke isn't quite old enough yet, but he's counting the days.

After the mayhem, the cars struggle back to base, where the crew only have a few minutes to resuscitate them in time for the next heat.

'Keith Boy' of the Southern Bandits isn't racing today, but he's come down to check out the competition. The rules state that no two cars should be painted the same colour, to avoid teams ganging up on one-another during the race. However, it seems that no one can resist.

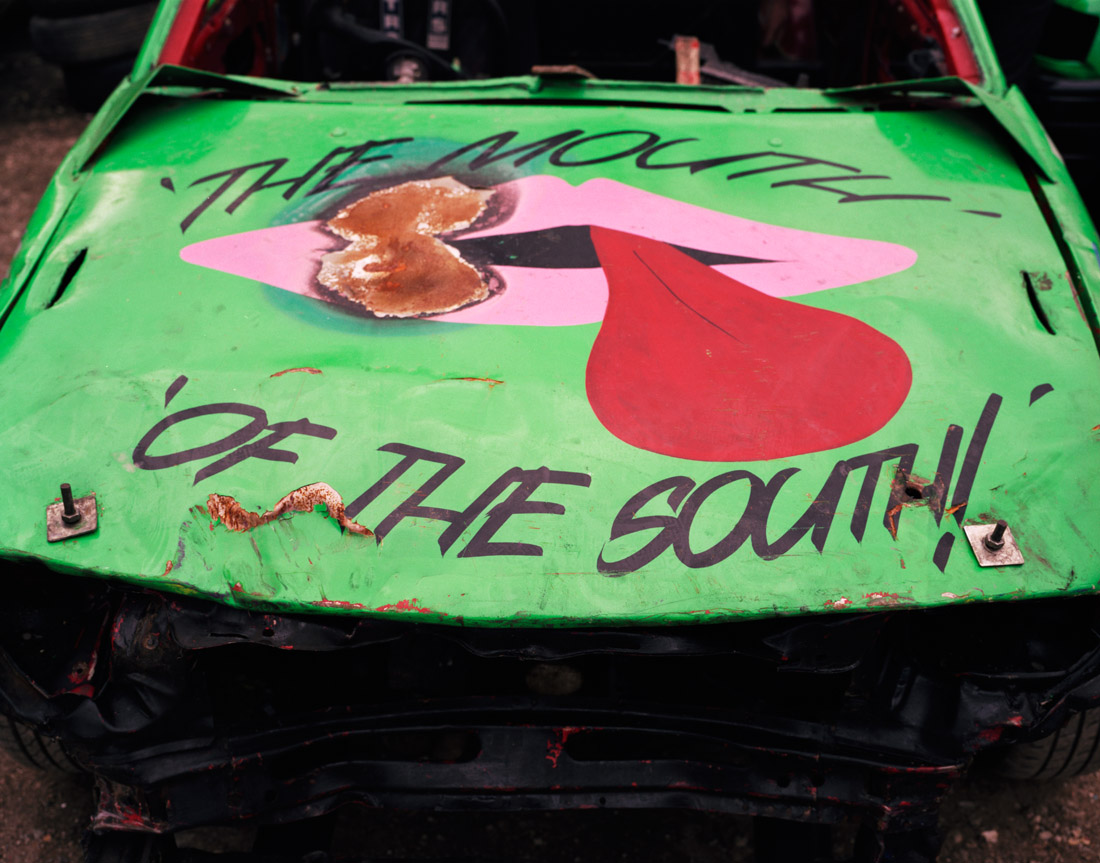

Jema "The Mouth of the South" at home. Jema's family now live ten minutes away from Aldershot Raceway. Before they moved, they used to work at traveling fairgrounds "like Carter's". Jason, Jema's brother, became good at fixing slot machines, now he makes bangers for her instead.

Some drivers spend many hours painstakingly decorating their cars. Jema flipped hers three times in the last race, so she's doubtful it will last much longer. However, she'll keep the bonnet, "I might even put it up in my bedroom, it's too good to throw."

Lacey May is one of the few girls that race with the boys.

Cars gather at the collection area before the stadium gates are opened.

A pause before the last race of the night.

The annual Darren Jones Benefit Gala in Ipswich raises money for a popular driver who was hit while stationary on the track eight years ago. Tonight he watches the races in his honour from a wheelchair, suffering from cerebral palsy after a lack of oxygen to the brain.

A mechanic works on his friend's banger, making sure it's ready for the last race of the night.

Some Banger racers talk proudly of how their home-grown sport has kept them off the streets, out of the pubs and away from trouble. Many invest hundreds of hours and thousands of pounds each year in doing up their cars and racing each week, leaving little space for anything else.

Once a banger is finally wrecked, the few parts that can be used again are salvaged, and the rest is sent to scrap. A moment's thought is spent on the battered car, until focus shifts to finding the next.